What kind of music was played in the Middle Ages?

In the Middle Ages, both sacral and secular music were performed. In the early stages, sacral music prevailed, later on more and more secular forms of music appeared. It is estimated that ca. 90% of all music performed during the early phases of the Middle Ages was sacral music, mostly in the form of chantings. Throughout the entire Middle Ages, sacral music had a huge significance overall! Music was not so much played for “the sake of playing” or showing of ones’ skills, or even to gain an income with it, but rather to honour God, Jesus Christ, or the Saints. Dancing music or dancing itself got more popular later on. Dances developed in the late medieval period, especially in France, Italy and Spain. Drums, Lutes, Bagpipes and other instruments appeared over the course of time and became part of the musical culture. The flute and different harp-type instruments, on the other hand, where known since the beginning throughout Europe. The medieval lute itself was a relatively late phenomenon within the Middle Ages and did not play a significant role at first. Before the lute showed up in Europe coming from the Arab world. Both, the citole and later on, the gittern, mattered much more in courtly and daily musical culture, as they were both native European inventions and thus were already known and integrated into the musical culture of the time.

Where and when was music commonly played in the middle ages?

For the sacral music, most of it was played (primarily sung) in churches and monasteries. Concerning secular music, it was more commonly played in courtly life, on fairs, markets, or within traveling minstrels’ and jesters’ programms.

What where some music – styles over the different phases of the middle ages?

A variation still known today is the Gregorian chant that was established on the early phases of the Middle Ages. It belongs into the category of monophonic music. During this phase, no notation system had been developed yet at all, other than some lines painted over lyrics, indicating prosody very loosely.

Later on, polyphonic music came into play. The polyphonic music was more complex and was the typical music of the high-medieval period. It ended in the late medieval period and knew several styles such as the Ars Antiqua, Ars nova and the Trovadorism/Minnesinger arose by its end. One of the main differences was that it already knew several forms of notation.

What forms of notation systems where used in the Middle Ages?

In the early phases of medieval music, there were no systems to depict scales, tones or notes. After the early medieval period there existed several systems that were progressing slowly into indicating the pitch of a vocal line, which were called neumes. This system were basically lines painted over the text of a song, thus indicaing the course of pitches in which the song operated. What it did not show, is a clear volume. After that, different stages of mesural notation followed.

The mesural notation looks much closer to our contemporary notation system, because it establishes lines into the notation for the first time, which makes it possible to write down melodies that are also for the sole purpose of instrumental music. Both systems evolved over time to become rather complex.

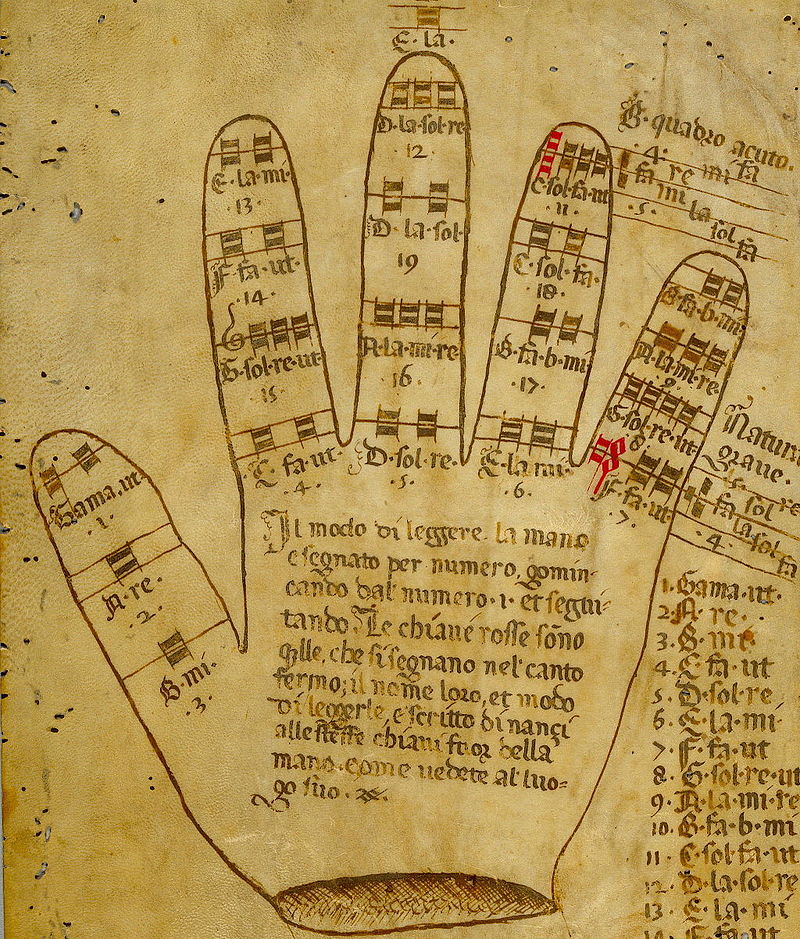

The first image shows an example of early neumes. The image below shows the more advanced mensural notation which looks a bit more familiar to us.

Source: Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neume

Source: Wikipedia

How were musical notes called in the Middle Ages?

In the middle ages, only six notes were known. They were called:

ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la, (si)*

*the seventh note si was added around the year 1500.

ut was what we would consider c

re was what we would consider d

mi was what we would consider e

fa was what we would consider f

sol was what we would consider g

la was what we would consider a

si was what we would consider h*

Did any lute tablature exist in the Middle Ages?

The correct answer is: Yes! In the late Middle Ages, the German Conrad Paumann (1410-1473) invented a basic lute tablature that would, later on, become the very fundation of Hans Neusiedlers‘ German Renaissance Lute Tablature. It, too, was based on the Latin alphabet. But, unlike in French Renaissance Tablature, it grouped the characters continuously over the fretboard, jumping across the strings (not staying consistant like in French Renaissance Tablature, meaning b always equals the first fret , c always equals the second fret, no matter what course is being referred to, etc.). Paumanns’ system used numbers to indicate the open strings (1 – 5), the alphabetic character /a/ startet in the first fret of the high g’ – string. The letters /u/ and /w/ were not included at all. The problem, though, was that if you applied the first alphabet, two frets remained empty, known as “et” and “con”. As a solution, the alphabet was started again, but with a distinguishable mark on the head of each character.

In my personal opinion, this system seems way to complicated to be taken into consideration for the tablature shown on The Medieval Lute Blog. On the other hand, the French Renaissance tablature is already used in some sources offering medieval songmaterial, using the Renaissance G-Tuning, mostly. Therefore I decided to work with numbers just as you would do in modern guitar tablature. As a result, the material offered on this blog becomes readable for everyone, even those without basic music- or – lute knowledge, which I find way more democratic! And, of course, since one of my main goals is to get more people to actually fall in love with this brilliant form of music and medieval plucked instruments in general, the access to it all ought to be somewhat low-threshold…

Source: Lex van Sante

Tablature

Modes/Scales

In the middle ages the Greek modes of music were integrated into church music.

Those modes are:

C – Ionian (C-D-E-F-G-A-H-c)

D – Dorian (D-E-F-G-A-H-C-d)

E – Phrygian (E-F-G-A-H-C-D-e)

F – Lydian (F-G-A-H-C-D-E-f)

G – Mixolydian (G-A-H-C-D-E-F-g)

A – Aeolian (A-H-C-D-E-F-G-a)

H – Locrian (H-C-D-E-F-G-A-h)

Gregorian authentic mode and plagal mode

Gregorian modes were used as mudical scales primarily during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. During the Renaissance though, they progressively became what we now know as major and minor scales. There are 12 Gregorian modes. Gregorian modes have a final, meanibh a note with which the melody ends. Its function was similar to that of the tonic in major and minor scales. Also, Gregorian modes have a dominant, which is sometimes denoted as “drone tone“, meaning they have a note that is most frequent throughout the melody (the basic tone underneath).

These modes are divided into two categories: authentic modes and plagal modes. Each plagal mode is associated with an authentic mode. Both have the same notes and the same Final. The difference between an authentic mode and its plagal is the dominant note.

Arrangement

Very much like in traditional Arabic music, European medieval music used concordance, especially before the 11th century. If you listen to bagpipe or hurdy-gurdy, you typically find one or several drone-tones or simply “drones” (also called “bourdon”) accompanying the entire piece. Before the upcoming of polyphonic music in the 11th century, melodies were simply arranged as single lines or doubled in striclty equal intervals throughout the piece, which means the same melody was played parallel, adding the Fourth- Fifth -or Octave. If certain parts of a song were emphasized, one would usually avoid playing the Second, Sixth, Seventh or Ninth of the main theme, but especially the Third (which was considered to be dissonant). Towards the end of a song, medieval musicians of that particular phase usually faded with an Octave or a Fith to the last main tone. Another method to fade a song, was to end at the same note together. From the 11th century onwards, the discantus was added to the cantus (“cantus” means “main voice” or “main melody”). The discantus was formed by creating a strictly non–concordant second melody-line in relation to the cantus, playing over the cantus “note-by-note”. The discantus was composed using the Prime, Fifth or Octave of each given note of the cantus. Later on, a second discantus-line was added, thus making the whole composition way more diversive and colorful. Over the decades, the discantus would also be more and more common whithin secular music.

Please keep in mind, that the tablature presented on this Blog almost completely depicts the cantus-form, meaning the main theme or melody of any given piece – whith the exception of most of the tablature shown in the segment “Advanced pieces” in which the cantus and the discantus can appear!

Chords

It is estimated that chords were used mainly in the late Middle Ages, e.g. in lute-plays and that before, the lute basically had played single -, or double-tone melodies.

The chords expanded in the late Middle Ages or early beginnings of the Renaissance, were suddenly augmented, diminished or dominant seventh chords, and other more complex figures showed up; probably enabled or faciliated by the appearance of the six-course lute. But the most signifcant change, by far, was the common use of the minor and major third, even in tunings.

Rhythm

During most of the early Middle Ages, no complex rhythms are estimated, because the main emphasis in medieval music was on the melodies, not as much on the rhythm. By the 12th century, a special form of courtly, and later on popular dance, called Istanpitta or Estampie, evolved. It was a kind of “stomp dance”, hence the rhythm played a more important role. Some more complex rhythms were also developed in the late 1300s, when polyphonic music came into more popularity. The most important composer of the Middle Ages is said to have been Guillaume de Machaut. What is known in terms of rhythm is, that bells, timbrels and rattles existed from early on in medieval Europe. Side drums, like the tabor, played with two drumsticks that sounded a little bit deeper than todays snare drums, appeared a bit later on. They were probably used to do very basic beats in non-military music and served for faster marches in military situations. Within churches or sacral music, almost no percussion instruments were probably used at all.

Source: Wikipedia